|

|

|

|

|

Exploring Subaltern Perspective in the Movie Kerry on Kutton: A Semiotic Analysis of Small-Town Realities in Indian Cinema

Harshit Kachhap 1![]() , Jayanta Kumar Panda 2

, Jayanta Kumar Panda 2![]()

![]()

1 Research

Scholar, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication, Berhampur University,

Odisha,

India

2 Associate

Professor, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication, Berhampur

University, Odisha, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Cinema in India often functions as

an ideological text that mirrors social realities, reinforces cultural

hierarchies, and constructs public perception of marginalised

communities. This study conducts a qualitative semiotic analysis of the Hindi

film Kerry on Kutton (2016) to examine how subaltern identities

are visually and narratively represented within the small-town socio-economic

landscape. Using a purposive sampling approach, the film was analysed through multiple viewing cycles, identifying key

signs, character trajectories, spatial settings and symbolic objects. Drawing

upon Saussurean and Barthesian

semiotics, the analysis proceeded through denotation, connotation and mythic

interpretation, while psychoanalytic and subaltern frameworks were employed

to contextualise character desire, humiliation and

aspiration. Findings reveal that the film encodes marginalisation

not through explicit dialogue, but through symbolic cues such as pig-rearing,

wedding band labour, leftover food, urban

aspiration and the gun as imagined emancipation. These narrative and visual

signs naturalises caste

hierarchies, structural poverty and the myth that upward mobility is

attainable only through deviance or violence. This study contributes to

existing scholarship by demonstrating how small-town Hindi cinema encodes

caste and class through symbolic and spatial cues rather than explicit

narrative exposition. The paper presents evidence that semiotic analysis can

reveal hidden ideological structures embedded in popular media. |

|||

|

Received 15 September 2024 Accepted 21 October 2025 Published 15 November 2025 Corresponding Author Harshit

Kachhap, hkachhap@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/ShodhVichar.v1.i2.2025.53 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Semiotics,

Subaltern Studies, Indian Cinema, Poverty Representation, Cultural Myth |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Cinema has long functioned as a cultural text through which societies narrate, contest, and reproduce their social realities. In the Indian context, scholars argue that film is not merely entertainment but an ideological apparatus that reflects and shapes public consciousness Ahmed (1992), Gupta and Gupta (2013). The representation of caste, class, love, poverty, and aspirations, particularly in small-town India, occupies a central position in contemporary filmmaking. While Indian cinema has often celebrated the lives of the privileged and urban elite, the lived experiences of marginalised communities have remained partially explored, frequently mediated through dominant-class storytelling. This gap has necessitated an examination of how films construct subaltern identities and the cultural meanings embedded in these portrayals.

Subaltern studies emerged as a critical academic effort to recover histories and voices that had been erased or simplified by elite historiography Guha (1989), Spivak (1996). The subaltern is not merely the “poor” or “weak”, but those structurally denied voice, dignity, and agency within social hierarchies. When cinema depicts characters who are marginalised by caste, occupation, or economic status, it participates in the same discursive process of representation. Therefore, films offer fertile ground for analysing how subalternity is visualised, normalised, or challenged in the cultural imagination.

Semiotics, the study of signs and meaning making, offers a systematic methodological lens for decoding such representations. As Saussure, Peirce, and Barthes have shown, meaning does not reside solely in language but in objects, gestures, colour, costume, architecture, and narrative form. A film can therefore communicate hierarchies without stating them directly, through the sight of a pig farm, a sewer-filled street, a torn uniform, or a gun held by a powerless youth. These visual and narrative codes help naturalise the ideological structures that organise social life. In parallel, psychoanalytic film theory enables us to understand how audience emotions, such as sympathy, identification, shame, or desire, are mobilised in shaping the perception of the subaltern Metz (1981), Freud and Chase (1925). Together, these frameworks enable a layered analysis of cinematic meaning.

Over the last decade, Hindi cinema has undergone a noticeable shift from metropolitan story worlds to small-town and rural narratives. Films such as Gangs of Wasseypur (2012), Masaan (2015), and Peepli Live (2010) foreground the precarity, humour, violence, and aspirations of rural and semi-urban youth in North India. Rather than presenting poverty through melodrama, these narratives attempt to depict structural marginality, informal labour, caste-coded social relations, and spatial segregation with documentary-like realism. Kerry on Kutton fits within this emerging cinematic tendency. Unlike the films mentioned above, which often feature narrative arcs that include moments of redemption, transformation, or social commentary, this film portrays mobility as unattainable. The film’s bleak trajectory, therefore, contributes to a growing genre of “hinterland realism” where subaltern youth are represented less as agents of change and more as casualties of systemic inequality. Scholars argue that this shift marks a departure from older Bollywood tropes of heroic transformation, replacing them with realist depictions of structural stagnation and the everyday violence of caste and class Chandra (2016), Dwyer (2020).

Kerry on Kutton (2016), directed by Ashok Yadav, presents a compelling narrative of four adolescents in Ballia, a small-town setting marked by poverty, ambition, caste restrictions, and moral ambiguity. The characters navigate a world that denies them dignity and opportunity, revealing how social hierarchy constrains mobility and identity formation. Despite its raw portrayal of everyday life, the film has received limited academic attention, and almost no published semiotic or subaltern analysis exists. This makes the text both relevant and timely.

Although Indian cinema has increasingly portrayed marginalised communities across various genres, a significant portion of these narratives continues to be framed through the gaze of dominant social groups. Mainstream films often aestheticise poverty, sensationalise violence, or reduce subaltern identities to comic relief, criminality, or victimhood. As a result, marginalised characters seldom emerge as complex individuals with agency, psychological depth, and socio-cultural nuance. In contrast, contemporary Hindi films, such as Slumdog Millionaire, Masaan, Gangs of Wasseypur, and Peepli Live, gesture toward subaltern realities; scholarly attention has remained limited, especially in the context of small-town youth navigating caste, poverty, aspiration, and humiliation.

Despite the film Kerry on Kutton (2016) presenting a vivid portrayal of subaltern life in rural Uttar Pradesh, combining symbols of caste-based labour, systemic deprivation and aspiration, no academic study has conducted a semiotic analysis of its narrative and visual codes. The absence of scholarly engagement with this film leaves a gap in understanding how marginalisation is encoded through cinematic structure, symbolic objects, psychoanalytic desire and cultural myth. This study seeks to fill that gap by examining the film not merely as entertainment, but as a socio-cultural text that constructs ideological meaning.

1.1. Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to decode how Kerry on Kutton visually and narratively constructs the subaltern condition through signs, symbols, narrative structure, and character psychology. By applying semiotics, supported by subaltern theory and psychoanalytic film theory, the research aims to uncover the deeper cultural messages embedded in the film’s representation of caste, poverty and aspiration. The study treats cinema as a meaning-making system, where objects, gestures, settings and conflicts function as signifiers that naturalise social inequality.

1.2. Research Objectives

In view of these conceptual and empirical concerns, the present study is guided by the following research objectives:

1) To analyse how Kerry on Kutton employs semiotic codes such as visual, symbolic and narrative elements to construct the subaltern identities of its characters.

2) To interpret the cultural meanings of caste, occupation, poverty and humiliation as communicated through cinematic signs, spatial settings and character interactions.

3) To examine whether the film challenges or reinforces dominant ideological stereotypes about marginalised communities within a subaltern and psychoanalytic framework.

2. REVIEW OF LITERATURE

2.1. Semiotics and Meaning-Making

Semiotics provides a foundational framework for analysing how cultural texts produce meaning through signs, symbols, and codes. Ferdinand De Saussure (1916) introduced the dyadic structure of the sign: the signifier (the material form) and the signified (the concept it evokes). According to Saussure, meaning does not exist naturally in objects; instead, it is socially constructed through language and cultural conventions. Expanding this view, Peirce (1934) proposed a triadic model of icon, index, and symbol to emphasise that signs acquire meaning through interpretation and context.

Barthes (1972) extended semiotics from linguistics to cultural objects, arguing that signs operate on two levels: denotation (literal meaning) and connotation (cultural/ideological meaning). At a further stage, signs take on the form of myth, transforming historically produced power and hierarchy into something “natural” and unquestioned. Barthes’ analysis is especially relevant to cinema, where ordinary objects such as costumes, gestures, spaces, and even food become carriers of ideological meaning. Eco (1979) similarly argued that visual communication relies on codes shared between creator and viewer, making cinema a “language system” that communicates far beyond dialogue.

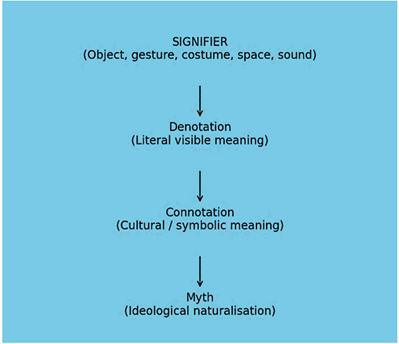

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Semiotic Model of Film Meaning |

Figure 1 illustrates the Semiotic model, which demonstrates how film signs transition from literal representation (denotation) to cultural meaning (connotation) and ultimately to ideological naturalisation (myth), as outlined by Barthes (1972) and De Saussure (1916).

2.2. Film Semiotics and Psychoanalytic Theory

Metz (1981) argued that cinema functions like a language, communicating subconsciously through mise-en-scène, framing, and narrative pattern. Film signs do not merely represent reality; they construct psychological identification. Metz’s concept of the “imaginary signifier” suggests that viewers project themselves into characters, experiencing emotion and desire through cinematic illusion.

Lacan (2014) mirror stage further extends psychoanalytic cinema theory. Viewers “see themselves” in characters, desiring their success, fearing their failure, or internalising their suffering. In films depicting marginalised communities, this identification can generate empathy while reinforcing social awareness of inequality. Mulvey (2001) adds a gendered dimension: the cinematic gaze reflects power structures, showing how dominant identities control representation. Although Mulvey writes about gender, her logic applies to caste and class in Indian cinema: who is seen, who is spoken, and who is silenced?

Eisenstein (2014) earlier demonstrated how montage and shot order manipulate audience emotion, meaning, and ideology. Mise-en-scène, colour symbolism, and sound design together create a multi-layered semiotic experience that shapes interpretation.

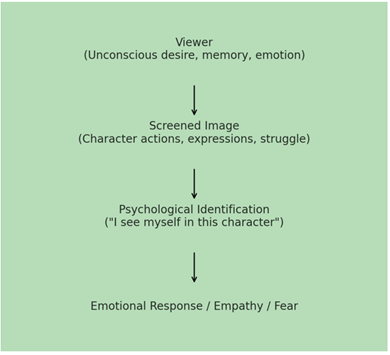

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Psychoanalytic Identification Process in Cinema |

Figure 2 shows how cinema facilitates audience identification with characters, thereby fostering emotional and psychological investment in them. Developed from Metz (1981) concept of the “imaginary signifier.”

2.3. Subaltern Studies and Representation

Subaltern Studies emerged to recover histories that had been erased by elite narratives Guha (1989). Rather than depicting people experiencing poverty as a homogeneous mass, subaltern theory emphasises the importance of attention to agency, culture, and lived experiences. Gramsci (2011) proposed the concept of cultural hegemony, in which the ruling class maintains power by naturalising inequality. In film, this means that oppression can appear “normal” or “inevitable,” not because it is explicitly stated, but because cinematic codes make it appear so.

Spivak (1996) and Spivak (2012) famously asked, "Can the subaltern speak?" Her answer was pessimistic; the subaltern voice is mediated, reshaped, or silenced by dominant ideological frameworks. In cinema, the subaltern seldom narrates their story; they are represented rather than representing themselves. Chatterjee (1993) and Chaturvedi (2000) emphasise that representation often reproduces elite viewpoints even when sympathetic.

Hauser et al. (1991) and Jaffrelot (1999) explain that Indian cultural production, such as literature, media, and cinema, often portrays marginalised communities either as victims or criminals, rarely as autonomous subjects. These debates are essential for analysing films like Kerry on Kutton, where symbolic labour, space, and humiliation become forms of structured silence.

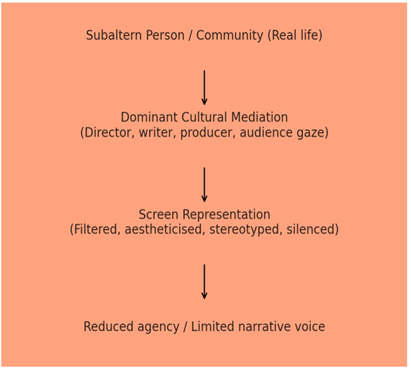

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Subaltern

Representation in Cinema |

As shown in Figure 3, the Model illustrates how subaltern identities are mediated through dominant cultural frameworks before appearing on screen, reflecting Spivak (1996) argument that the subaltern rarely speaks directly.

2.4. Caste Hierarchy and Poverty in Indian Society

The subaltern condition in India cannot be analysed without acknowledging caste. Ambedkar (1946) argued that caste is a system of graded inequality shaping labour, dignity, rights, and access to public life. Sen (1982), Duflo and Banerjee (2011) demonstrate that poverty is not merely economic deprivation; it is a structural exclusion deeply tied to caste, education, and access to public resources.

Sociological accounts show that caste-linked occupations (such as cleaning, band-playing, slaughtering animals, and manual scavenging) are transmitted generationally. Studies by Sharma (2015) and Guha (1989) reveal that humiliation is not incidental but institutionally embedded in everyday practices, such as food segregation, separate seating, spatial exclusion, or denial of public dignity.

Cinema participates in this discourse. Gupta and Gupta (2013) found that Indian films often aestheticise poverty, turning suffering into spectacle. Mulvey (2001) refers to this as a “politics of looking,” where audiences visually consume marginalisation. Films like Slumdog Millionaire or Peepli Live show people with low incomes but seldom transform their conditions; they are seen but not heard.

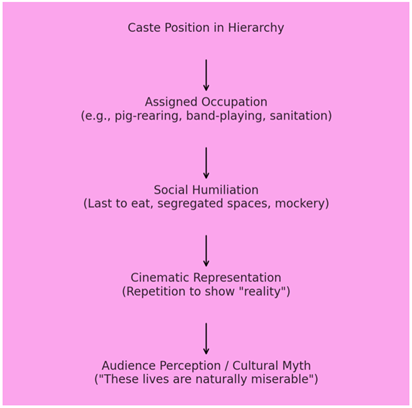

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Caste, Labour, Humiliation, and Screen Portrayal |

Figure 4 illustrates how caste-linked labour produces structural humiliation, which cinema often portrays as a natural reality, thereby reinforcing cultural myths Ambedkar (1946), Sen (1982), Gramsci (2011).

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This study adopts a qualitative research design grounded in semiotic analysis to interpret the subaltern representation in the film Kerry on Kutton. Films are complex visual texts, and their meaning is encoded through symbols, narrative choices, character behaviour, setting, and cinematic style. Since semiotics deals with the study of signs and the process through which meaning is produced and interpreted, it offers a suitable methodological lens for analysing marginalisation, power structures, and cultural hierarchies depicted on screen. The intention of the analysis is not merely to describe cinematic scenes, but to decode how specific visual and narrative elements communicate socio-cultural messages.

The film Kerry on Kutton (2016) was selected through purposive sampling. It represents a typical small-town socio-economic environment, featuring characters embedded in caste-based occupations, poverty, and social humiliation, making it an appropriate text for subaltern interpretation. The unit of analysis includes scenes, dialogues, objects, background elements, and technical features such as colour tones or framing. The researcher viewed the film multiple times to gain a comprehensive understanding of the storyline and subsequently to identify relevant signs and patterns. Significant scenes were captured as screenshots and catalogued along with their context to maintain analytic traceability.

The semiotic analysis followed a two-layer coding process inspired by Ferdinand de Saussure and Roland Barthes. In the first stage, denotative (literal) meanings of signs were identified, for example, pigs, sewers, or a wedding band. In the second stage, the connotative meaning was interpreted by examining how such images relate to caste hierarchy, humiliation, class identity, and aspirations. Finally, these signs were analysed at the mythic level, where the more profound cultural messages, such as the idea that lower-caste labour is impure or that upward mobility requires violence, were interpreted. The analysis also employed narrative coding to study character arcs, story progression, and conflict, since marginalisation is often communicated through a character’s emotional and social journey.

To strengthen analytical depth, insights from psychoanalytic film theory and Marxist-subaltern scholarship were integrated. Psychoanalysis was applied to interpret characters’ desires, insecurities, and the psychological dimensions of their decisions. In contrast, Marxist and subaltern frameworks helped decode the power relations embedded in occupation, caste, and social behaviour. This interdisciplinary approach allowed a holistic reading of the film as a socio-cultural text rather than a purely fictional narrative.

Maintaining credibility in qualitative research requires a systematic and reflexive approach to engaging with data. Therefore, the researcher repeatedly cross-checked scenes, symbols, and interpretations with theoretical literature, ensuring that meanings were not derived solely from personal assumptions. Triangulation was achieved by comparing the cinematic depiction of caste and poverty with scholarly literature in film studies, anthropology, and subaltern histories. Analytical notes were maintained throughout the viewing process to document emerging patterns and avoid retrospective bias.

4. FINDINGS

The findings of this study are organised around three analytical categories derived from the research objectives: (1) semiotic construction of subaltern identity, (2) cultural meanings encoded through symbols and spaces, and (3) ideological positioning of marginalised communities within the narrative.

To ensure analytical consistency and avoid subjective over-interpretation, every selected scene was documented in a semiotic coding sheet. For each visual frame, the denotative elements (objects, lighting, space, costume, and body posture), connotative meanings (cultural interpretation and symbolic value), and mythic readings (normalised ideologies of caste, labour, or impurity) were recorded systematically. This process allowed the movement from literal observation to cultural interpretation to remain transparent. A simplified version of the coding structure used in this study is presented in Table 1.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Semiotic Coding Structure Used for Analysing Visual Scenes in Kerry on Kutton. |

|||

|

Scene |

Denotation |

Connotation |

Ideological Message |

|

Pig-rearing (Kerry’s family business) |

Kerry is feeding pigs on the farm |

Occupation associated with impurity and caste

stigma |

Lower caste labour = social inferiority; mobility

blocked |

|

Band-Baza profession |

Kadambari’s father plays the band at weddings |

Low-income caste-based profession, servitude |

Subalterns serve, elites

celebrate; power hierarchy normalised |

|

Last to receive food at the wedding |

Band members wait after guests finish eating |

Humiliation through ritualised hierarchy |

Subaltern must accept leftovers; dignity denied |

|

Sewer-filled neighbourhood |

Dirty pathways in Kerry’s locality |

Neglect, lack of infrastructure |

Poverty is systemic, not accidental |

|

Gun as a symbol |

Kadambari sees a gun as a ticket to wealth |

Violence is perceived as the only escape |

The system is so closed that only crime offers

mobility |

4.1. Semiotic Construction of Subaltern Identity

The film constructs subaltern identity primarily through visual symbols, occupation, and bodily markers that indicate caste-based labour. Kerry’s association with pig-rearing operates as one of the strongest semiotic codes in the narrative. Pigs are not presented as neutral animals but as cultural signifiers connoting impurity, social inferiority, and manual labour. Throughout the film, Kerry’s identity is inseparable from the pig farm, suggesting that caste and occupation remain structurally fused.

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Kerry Feeds His Pig in His Pig Farm. Screenshot Captured by the Author from Kerry On Kutton (2016) |

In this scene, Kerry stands inside a muddy enclosure, throwing food scraps toward pigs. His clothes appear worn and soiled, and the enclosure is surrounded by stagnant water, broken fencing, and scattered garbage. No background music or dialogue is present; only the loud grunting of pigs dominates the soundscape. The frame is held in a medium-long shot, emphasising Kerry’s body and the animals occupying the same physical space.

At a denotative level, the scene simply shows a boy feeding pigs. Connotatively, pig-rearing in the Indian cultural context is strongly associated with impurity, pollution, and lower-caste labour. When read mythically, the scene naturalises the idea that Kerry’s identity is inseparable from waste, dirt, and social exclusion. By visually collapsing the human and animal spaces, the film constructs Kerry as someone who belongs outside the moral and physical boundaries of society.

Similarly, Kadambari’s involvement in the wedding band business signifies a form of inherited servitude. Even without explicit dialogue about caste, the film uses clothing (uniform), physical exhaustion, and subservience to encode marginality. The characters are consistently positioned as workers in the background of celebratory spaces, reinforcing their invisibility.

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Kadambari's Father Insisted that He Join his Family Business. |

Figure 6 shows that Kadambari has joined as a band party member in his father’s family business, leaving his studies. This demonstrates occupational inheritance and symbolic inferiority. Taken together, these codes operate as narrative shorthand to communicate that marginalisation is not chosen but culturally imposed.

4.2. Cultural Meanings Encoded in Signs, Spaces, and Interactions

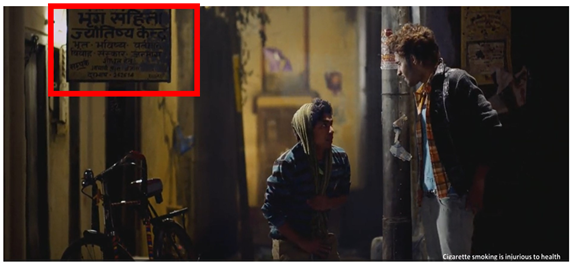

Spatial settings function as semiotic landscapes that visually separate the privileged from the subaltern. Kerry’s neighbourhood is depicted through narrow streets, broken drains, stagnant sewage water, and dilapidated walls. In contrast, Jyoti’s locality displays cleaner streets, well-painted houses, and the presence of professional signage such as the astrologer’s banner. These contrasting spaces operate as visual evidence of unequal access to dignity and infrastructure.

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 Sewage-Filled Lane in Kerry’s Locality. |

The camera follows the boys as they walk through a narrow passage filled with open drainage, plastic waste, and stagnant water. The lighting is dim, and the houses appear unfinished or crumbling. The characters are positioned near walls, often stepping aside to make room for others who pass.

Denotatively, this is a street in a small, congested town. Connotatively, the dirt, sewage and cramped movement signify social marginality; these are not public spaces of dignity but spaces of containment. At the mythic level, such visuals naturalise the idea that the subaltern belongs to dirty, decaying spaces. The environment becomes a silent marker of structural inequality: smallness, waste, and bodily discomfort operate as semiotic codes that reflect social hierarchy.

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 Astrology Banner in Jyoti’s Locality. |

Together Figure 7 and Figure 8 contrasts backwardness with relative privilege, without requiring verbal exposition.

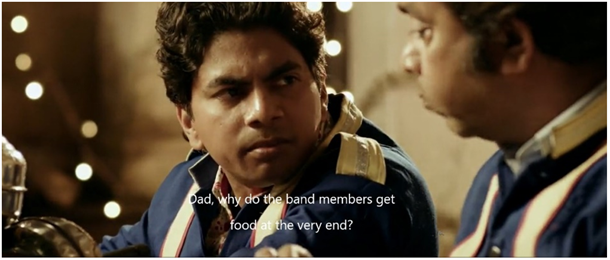

Food hierarchy appears as another symbolic system. In a wedding sequence, band members are served last, after all guests have finished eating. At the denotative level, this is a dining arrangement; at the connotative level, it is ritualised humiliation. The scene implies that those who produce and serve entertainment remain structurally excluded from participation, reflecting caste-coded exclusion in public spaces.

Figure 9

|

Figure 9 Kadambari Questioning His Father About Being Served Last, Screenshot Captured by the Author from Kerry on Kutton (2016) |

The gun functions as a mythical object representing escape from poverty. Kadambari repeatedly asserts that wealth requires an “extra force”, implying that legal routes to social mobility are blocked for people experiencing poverty. The firearm does not merely represent violence; it symbolises the belief that resistance is the only path to dignity when the system offers none.

Figure 10

|

Figure 10 Screenshot of a Childhood Scene of Rajesh Firing the Gun. |

This reinforces Barthes’ proposition that signs become myths, turning a real object into an ideological message.

In several scenes, Kerry keeps an old, rusted revolver hidden inside his clothes. The gun is revealed in medium close-ups, with the camera focusing on his trembling hands as he grips it. The weapon is often shown in isolation, even without firing, resting beneath his pillow, inside his waistband, or held against another character. No adult authority figure is present; the boys handle the weapon unsupervised, whispering about its potential power.

Denotatively, the scene shows a boy holding a gun. Connotatively, the weapon functions as a shortcut to dignity, masculinity, and revenge, elements that the boys cannot access through legal or social means. At the mythic layer, the gun symbolises the fantasy of liberation in a world where institutional justice is absent. It becomes the only tool through which the subaltern can imagine equality with dominant groups. However, because the gun repeatedly fails to produce empowerment, the myth collapses, reinforcing the idea that subaltern agency is structurally impossible.

4.3. Ideological Positioning of the Subaltern in the Narrative

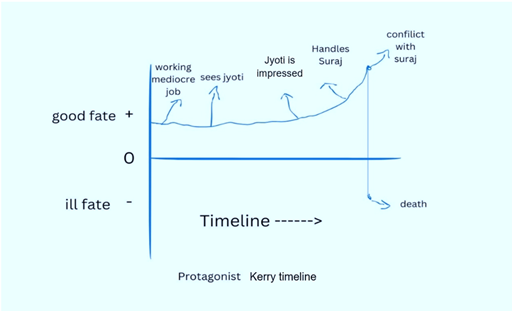

Narrative structure serves as the final semiotic layer. Each character aspires to mobility. Kerry seeks romantic acceptance, Kadambari hopes for economic success, and Suraj searches for social recognition. However, these desires gradually collapse under the weight of structural violence. The screenplay repeatedly raises the possibility of transformation, only to withdraw it at the crucial moment. This pattern is not presented as personal failure, but as a social inevitability. The narrative punishes aspiration itself, suggesting that the subaltern imagination cannot convert hope into change. In this sense, the film mirrors Metz’s observation that cinema first invites identification with marginalised characters and then forces the audience to witness their defeat. It also resonates with Spivak’s argument that the subaltern speaks, but their voice is either ignored, criminalised, or destroyed. The absence of any institutional rescue, such as a teacher, political representative or community support, indicates that systemic oppression remains unchallenged. The characters can desire and dream, but they cannot escape their fate.

Figure 11

|

Figure 11 Timeline Illustrating the Protagonist’s Rise and Fall |

Figure 11 demonstrates Metz’s claim that audiences identify emotionally with subaltern characters, only to witness their inevitable defeat. It also reinforces Spivak’s argument: the subaltern attempts to speak, but their speech (desire, anger, romance) leads to destruction rather than liberation.

Moreover, the absence of any transformative character or institution, no teacher who uplifts, no political intervention, and no community resistance indicates that systemic oppression remains unchallenged. The subaltern exists only to suffer, aspire, and fail.

5. DISCUSSION

5.1. Occupation as a Semiotic Marker of Caste and Subaltern Identity

The film employs occupation as its most visible semiotic device for constructing subaltern identity. Kerry’s association with pig-rearing and Kadambari’s involvement in the wedding band are not random professional choices, but they are culturally coded signs that Indian society links to hereditary caste labour. Without the need for explicit dialogue, these professions function as Barthesian myths: common visual signs that carry deep cultural meaning about purity, social worth, and economic inferiority. In the Indian social hierarchy, pig-rearing is associated with communities historically relegated to “polluting” work, while wedding band labour is coded as a low-status service occupation. Through Saussure’s signifier–signified structure, these scenes inform the audience that caste and labour remain intertwined and inherited.

From a subaltern perspective, this representation reinforces Ranajit Guha’s argument that marginalised communities are historically defined through labour rather than voice. The characters work in spaces of celebration but never participate in that celebration, indicating their structural exclusion. Their bodies serve the dominant castes, but their identities remain invisible to them. Spivak’s question, “Can the subaltern speak?” emerges clearly here: the characters labour, sweat, serve, and endure humiliation, yet they never narrate their own condition. The silence surrounding their profession is, in itself, a form of oppression. Thus, the film uses occupation not only as background detail, but as a semiotic tool to encode caste, power and invisibility.

5.2. Spatial Hierarchy as a Visual Sign of Social Exclusion

Spatial settings in the film operate as symbolic landscapes that reflect a stratified social order. Kerry’s locality is contrasted with Jyoti’s not through dialogue, but through the presence or absence of infrastructure: broken drains, stagnant sewage, narrow lanes, versus cleaner streets and signage. Barthes asserts that myth transforms history into a natural phenomenon. Here, the cinematic framing turns inequality into something that feels “ordinary” and expected. The audience is meant to recognise Kerry’s world instantly, as if squalor is naturally associated with poverty.

This aligns with Gramsci’s idea of hegemonic common sense, where social inequality becomes so deeply embedded that it appears normal and inevitable. The film’s refusal to depict institutional presence, such as the absence of government schools, social workers, and political voices, suggests a world where the state does not exist for the subaltern. The space itself becomes a sign of abandonment.

The sewage-filled streets, therefore, do more than create a setting; they visualise the caste-linked idea of “pollution,” implying that those who live with impurity are believed to be polluted. In this way, the camera reproduces an ideology without direct commentary. This is a subtle but powerful example of how films naturalise exclusion through spatial design.

5.3. Hierarchies of Food and Public Humiliation

Among all symbols, food offers one of the clearest illustrations of social distance upheld through ritual behaviour. In the wedding scene where band members are served last, the film encodes humiliation within a simple act of waiting. The denotation (receiving food after others) becomes connotation (structural inferiority), and finally myth (the belief that those who serve deserve less). Barthes states that everyday objects and actions become mythic when they reinforce dominant ideology; here, the scene communicates that dignity is a privilege, not a right.

Subaltern theory often highlights how discrimination is not always spectacular; it is embedded in daily interactions. The delay in receiving food is a cinematic re-enactment of caste-based exclusion in access to water, temple entry, and public eating spaces in rural India. The scene, therefore, extends beyond narrative realism and becomes a cultural statement: humiliation is not episodic, but systemic.

5.4. The Gun as Myth of Emancipation and Psychoanalytic Desire

While most symbols in the film express subordination, the gun symbolises the fantasy of power. Kadambari repeatedly asserts that people with low incomes can only rise through force, suggesting that lawful mobility is denied to them due to their social location. This aligns with psychoanalytic film theory, which argues that objects represent unspoken desire. The gun becomes a compensatory object, a psychological substitute for dignity.

Barthes would describe this as a cultural myth: the belief that violence offers liberation. The myth does not emerge from individual imagination, but from the collective experience of structural powerlessness. The film shows how deeply such myths shape the behavioural choices of marginalised youth. Even though violence ultimately destroys the characters, the myth persists because the system provides no alternative path to dignity.

This also reinforces Spivak’s proposition: when the subaltern attempts to “speak,” their voice takes the form of violence, which is then condemned by society, creating a cycle in which the subaltern is silenced both for suffering and for resisting.

5.5. Narrative Defeat and the Inability of the Subaltern to Transcend Structure

Although the characters are emotionally compelling, the narrative offers no route to transformation. Every aspiration, such as love, wealth, and dignity, collapses into tragedy. This reflects Gramsci’s concept of “hegemony of despair,” where the oppressed internalise the belief that change is impossible. Metz describes this as psychoanalytic identification: audience members recognise themselves in the protagonist’s suffering, only to witness their inevitable defeat.

The significance of this narrative structure is political. When films repeatedly portray people with low incomes as unable to win, they perpetuate a cultural myth that structural injustice is permanent. The absence of teachers, leaders, institutions, or collective resistance reinforces a worldview in which oppression is perceived as unchangeable.

This narrative choice aligns with Spivak’s claim that the subaltern does not speak, not because they lack language, but because their voice has no effect. Desire becomes self-destructive, aspiration becomes violence, and resistance becomes death. Ultimately, the film portrays survival, rather than emancipation.

Across all themes, Kerry on Kutton relies on semiotic density, including objects, spaces, labour, humiliation, and tragedy, to convey the subaltern condition. The film’s visual language renders caste a tangible presence and poverty a lived experience. However, its narrative structure reinforces the idea that liberation is unavailable to the marginalised, thereby reproducing the ideological constraints that subaltern theory criticises.

6. CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates that Kerry on Kutton functions as a dense semiotic text through which subaltern identity, caste-coded labour, and structural poverty are visually and narratively constructed. Rather than relying on explicit dialogue, the film encodes marginalisation through symbolic objects, spatial hierarchies, bodily labour and repetitive humiliation. Using a Saussurean and Barthesian framework, the analysis showed that signs such as pig-rearing, wedding band uniforms, sewer-filled lanes, and the gun operate as culturally loaded symbols. These signs travel from denotation to connotation to myth, ultimately naturalising caste hierarchy and normalising the idea that the poor remain trapped in inherited social positions.

The narrative trajectory reinforces this ideological construction. While each character aspires to dignity, economic mobility or emotional validation, their journeys end in defeat, violence or death. In psychoanalytic terms, desire becomes a site of frustration and destruction rather than a source of empowerment. Metz argues that cinema encourages viewers to identify with on-screen characters; however, in this film, identification leads the audience toward emotional investment without offering resolution or transformation. The absence of institutional support, collective resistance, or alternative pathways reflects the structural reality of marginalised communities, for whom mobility is often imagined but seldom achieved.

From a subaltern theoretical standpoint, the film confirms Spivak’s assertion that the subaltern rarely “speaks” within dominant representational systems. The characters do not acquire voice, dignity, or agency; instead, their labour sustains others’ celebration, their spaces remain neglected, and their aspirations are criminalised. In this way, the film reflects Gramsci’s concept of hegemony, where inequality becomes so culturally ingrained that it appears natural and inevitable. As a result, Kerry on Kutton simultaneously exposes and reproduces the structures of caste and class oppression that it seeks to depict.

While the film offers an unfiltered portrayal of small-town deprivation, its representational politics raise critical questions. Does witnessing subaltern suffering create awareness, or does it aestheticise inequality for cinematic impact? The analysis suggests that the film generates empathy but stops short of offering narrative agency or ideological challenge. It reflects reality with accuracy, yet offers no imagination of liberation.

Overall, this study affirms that semiotic analysis provides a powerful methodological tool for understanding cinema as a cultural and ideological apparatus. Films do not merely represent society, but they actively shape how viewers understand marginalisation, caste, desire, and power. By decoding visual and narrative signs, scholars can uncover how cinematic texts participate in the reproduction of social hierarchies. Future research may extend this inquiry by comparing multiple films, incorporating audience reception, or analysing how digital platforms reshape subaltern narratives in contemporary India.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None .

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, A. S. (1992). Bombay Films: The Cinema as a Metaphor for Indian Society and Politics. Modern Asian Studies, 26(2), 289–320. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X00009793

Allen, G. (2004). Roland Barthes. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203634424

Ambedkar, B. S. (1946). What Congress and Gandhi did to the Untouchables. Gautam Book Center.

Azevedo, J. P. (2020). Learning poverty: Measures and simulations. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-9446

Barthes, R. (1972). Mythologies. Hill and Wang.

Bazin, A., and Cardullo, B. (2011). André Bazin and Italian Neorealism. AandC Black.

Bouzida, F. (2014). The Semiology Analysis in Media Studies: Roland Barthes' Approach.

Campbell, J. (2003). The Hero’s Journey: Joseph Campbell on hiS Life and Work (Vol. 7). New World Library.

Chakrabarty, D. (2018). Rethinking Working-Class History: Bengal 1890–1940. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv3hh57s

Chandra, S. (2016). Hinterland Masculinity and Youth Imaginaries in Gangs of Wasseypur. South Asian Popular Culture, 14(2), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2017.1294808

Chatterjee, P. (1993). The Nation and its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691201429

Chaturvedi, V. (2000). Mapping Subaltern Studies

and the Postcolonial. Verso.

Culler, J. D. (1986). Ferdinand de Saussure.

Cornell University Press.

De Saussure, F. (1916). Nature of the Linguistic Sign. In Course in General Linguistics

(pp. 65–70).

Duflo, E., and Banerjee, A. (2011). Poor Economics. PublicAffairs.

Dwyer, R. (2020). Bollywood's new Realism: Urban Margins and Small-Town Narratives. Journal of Contemporary Film Studies, 12(3), 44–59.

Eagleton, T. (2014). Ideology. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315843469

Eco, U. (1979). A Theory of Semiotics (Vol. 217). Indiana University Press.

Eisenstein, S. (2014). Film Form: Essays in Film Theory. HMH.

Field, S. (2005). Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Delta.

Freud, S., and Chase, H. W. (1925). The Origin and Development of Psychoanalysis: Sigmund Freud’s Lectures at Clark University, 1910 [Lecture translation]. https://doi.org/10.1037/11350-001

Gallop, J. (1982). Lacan's “Mirror Stage”: Where to Begin. SubStance, 11, 118–128. https://doi.org/10.2307/3684185

Gibbs, J., and Gibbs, J. E. (2002). Mise-En-Scène: Film

Style and Interpretation (Vol. 10). Wallflower Press.

Gramsci, A. (2011). Prison notebooks (Vol. 2). Columbia University Press.

Gramsci, A. (2020). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. In The Applied Theatre Reader (141–142). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429355363-27

Greimas, A. J. (1971). Narrative grammar: Units and Levels. MLN, 86(6), 793–806. https://doi.org/10.2307/2907443

Guha, R. (1989). Subaltern Studies VI: Writings on South Asian History (Vol. 6). Oxford University Press.

Gupta, S. B., and Gupta, S. (2013). Representation of Social Issues in Cinema With Specific Reference to Indian Cinema: Case Study of Slumdog Millionaire. The Marketing Review, 13(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1362/146934713X13747454353619

Harman, G. (1977). Semiotics and the Cinema: Metz and Wollen. Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 2(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509207709391329

Hauser, W., Guha, R., and Spivak, G. C. (1991). Selected Subaltern Studies. The American Historical Review, 96(1), 241. https://doi.org/10.2307/2164184

Huppatz, D. J. (2011). Roland Barthes, Mythologies. Design and Culture, 3(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.2752/175470810X12863771378833

Jaffrelot, C. (1999). The Hindu Nationalist Movement and Indian Politics: 1925 to the 1990s. Penguin Books India.

Lacan, J. (2014). The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience. In Reading French psychoanalysis (pp. 97–104). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315787374-6

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1975). Anthropology: Preliminary Definition: Anthropology, Ethnology, Ethnography. Diogenes, 23(90), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/039219217502309001

Lévi-Strauss, C. (2003). Myth and Meaning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203164723

Metz, C. (1981). The Imaginary Signifier:

Psychoanalysis and the Cinema.

Indiana University Press.

Mulvey, L. (2001). Unmasking the Gaze: Some Thoughts on New Feminist Film Theory and History. Lectora: Revista de Dones i Textualitat, 7, 5–14.

Olcott, M. (1944a). The Caste System of India. American Sociological Review, 648–657. https://doi.org/10.2307/2085128

Peirce, C. S. (1934). Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce (Vol. 5). Harvard University Press.

Perry, G. (2006). Poverty Reduction and Growth: Virtuous and Vicious Circles. World Bank Publications. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-6511-3

Rohima, S., Suman, A., Manzilati, A., and Ashar, K. (2013). Vicious Circle Analysis of Poverty and Entrepreneurship. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 7(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.9790/487X-0713346

Sarkar, S. (1989). Modern India 1885–1947. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-19712-5

Sebeok, T. A. (2001). Signs: An Introduction to Semiotics. University of Toronto Press.

Sen, A. (1982). Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198284632.001.0001

Sharma, S. (2015). Caste-Based Crimes and Economic Status: Evidence from India. Journal of Comparative Economics, 43(1), 204–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2014.10.005

Spivak, G. C. (1996). The Spivak Reader: Selected Works of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Routledge.

Spivak, G. C. (2012). Subaltern Studies: Deconstructing Historiography. In In other Worlds (270–304). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203441114-21

Sterritt, D. (1999). The Films of Jean-Luc Godard: Seeing the invisible. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511624322

Thurschwell, P. (2009). Sigmund Freud. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203888063

Van Ginneken, J. (1992). Crowds, Psychology, and Politics, 1871–1899. Cambridge University Press.

Vogler, C. (2017). Joseph Campbell Goes to the Movies: The Influence of the Hero's Journey in Film Narrative. Journal of Genius and Eminence, 2(2), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.18536/jge.2017.02.2.2.02

Worth, S. (1969). The Development of a Semiotics of film. In Studying Visual Communication (36–73). University of Pennsylvania Press.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhVichar 2025. All Rights Reserved.